Many teachers wait until late winter or spring to begin teaching poetry, prose, and drama, and it’s always a refreshing change of pace. I like to begin after I teach figurative language, because students have a reference point to relate to during instruction. In this post, I’ve shared my favorite lessons for teaching poetry. You can find the lessons below in this reading unit.

At the beginning of the study on poetry, students focus on stanzas, verse, and meter. To show students examples of the elements of poetry, you may use almost any poem. The poems I have selected are “meaty” poems, so students must read and reread the poems to analyze the multiple layers of meaning.

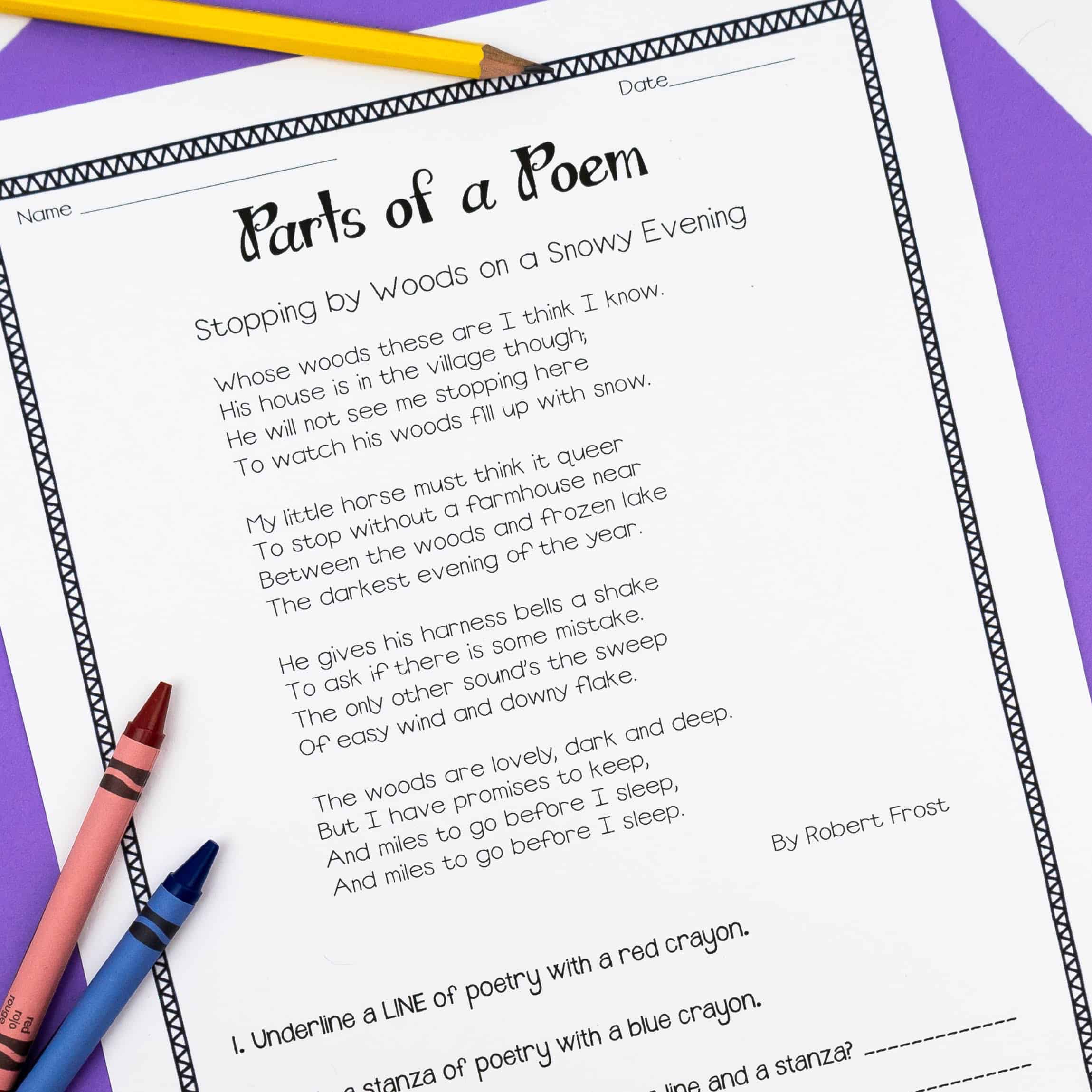

Parts of Poem

Students first need to learn HOW to read a poem, as well as the parts of a poem. It’s important to explain that poems are written using lines and stanzas. Make sure that students understand that lines are not necessarily complete sentences and that lines do no always go all the way across the page. Then, show students that a group of lines is a stanza. Explain that a stanza is group of lines in a poem, separated by space from other stanzas, much like a paragraph in prose.

It’s important for students to know that we do not read poems the same way we read a book or article. Poems can have many layers and many meanings, so we need to read the poem multiple times. The first time you read a poem, concentrate on just reading the poem. After you read the poem, try to determine the meaning of any words you don’t know. Reread the poem out loud so you can hear the poem, which will help you understand the poem. When you are reading, don’t pause at the end of each line, which could cause the poem to sound choppy. Instead, pause only where there is punctuation, just as you would when reading prose, only more slowly. Be sure to model how to read slowly and clearly.

Free Verse

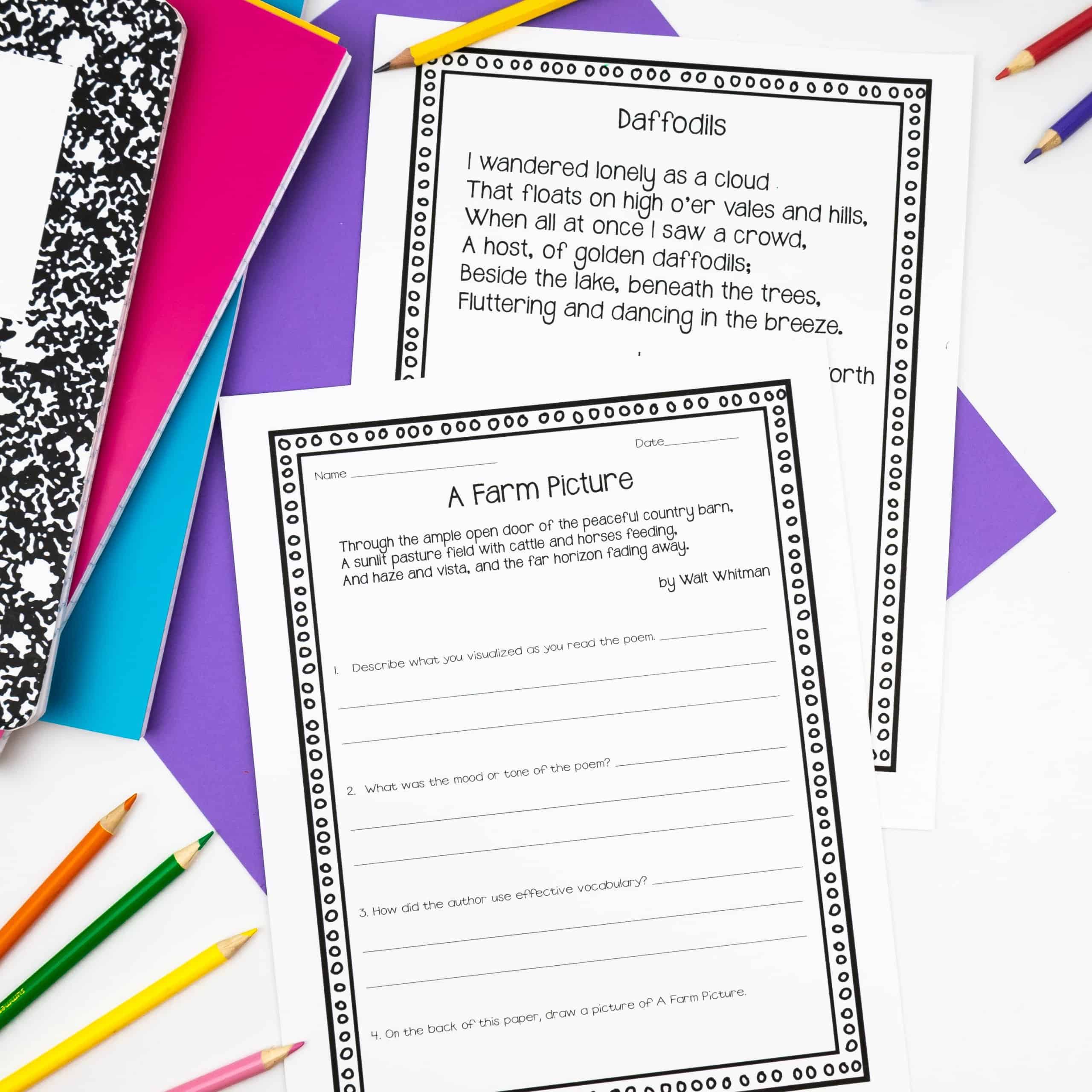

Before focusing on more complex poetry structures, I introduce free verse poems. As we ease into the comprehension of poetry, this frees students to focus on the meaning, rather than overly focusing on structure. Students often have the misconception that poems must rhyme, which isn’t the case at all. It’s necessary to teach students there are many different types of poetry. One common form is called free verse where there is no rhyme scheme or set pattern.

Read “Daffodils” or “Farm Pictures” and have students to discuss the poem in a small group. Ask students what they visualized as you read and discuss how the author used imagery within the poem, as well as the author’s choice of words and how they impacted the text.

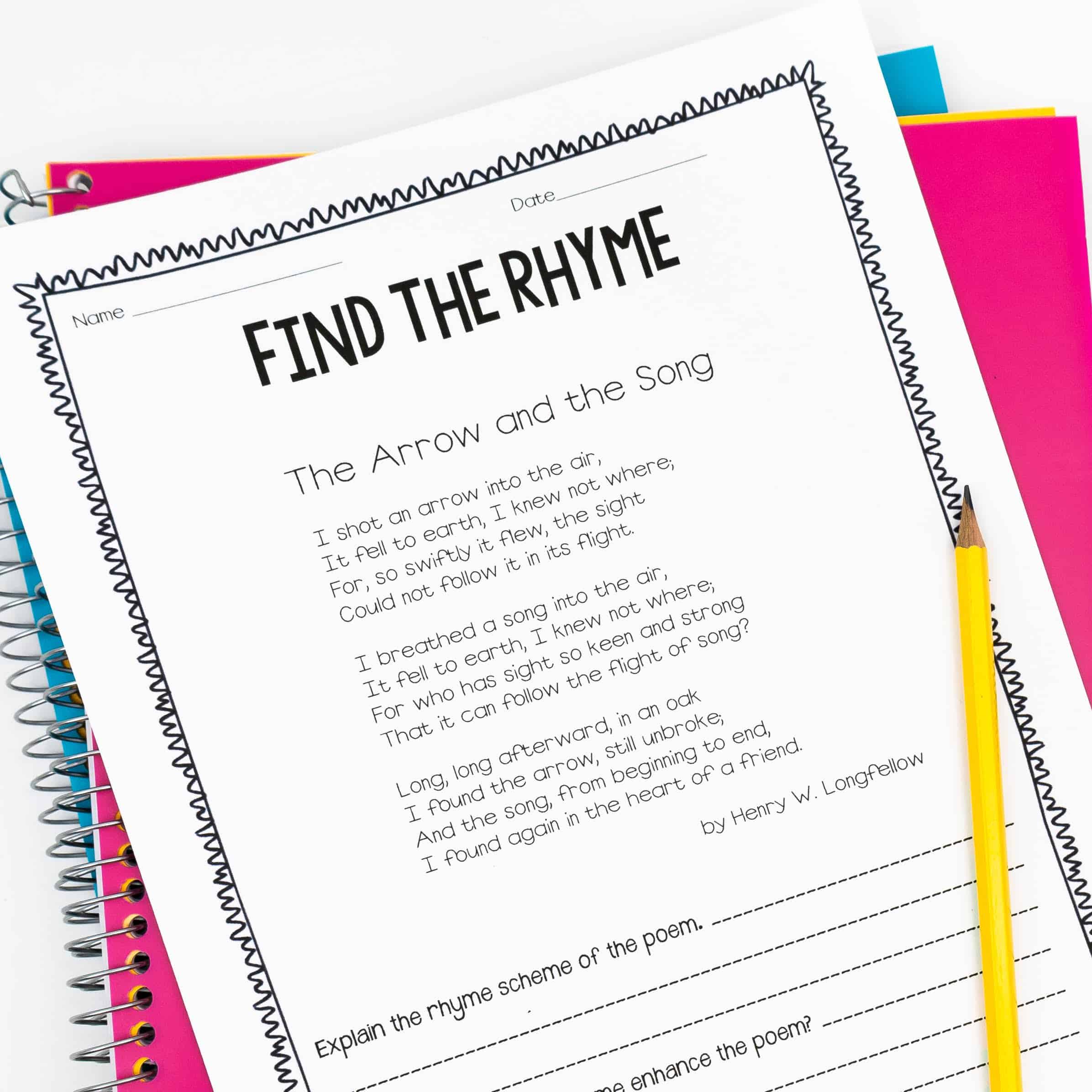

Rhyme & Meter

Once students are comfortable reading and interpreting free verse poems (which typically isn’t long) you can introduce rhyme schemes. There are three main reasons an author chooses to make his/her poem rhyme: 1. To give pleasure. Rhyme is pleasing to the ear. It adds a musical element to the poem and makes the pieces fit together; 2. It makes a poem easier to memorize; 3. To deepen meaning. I like to have students work together to find the rhyme scheme of the poem(s).

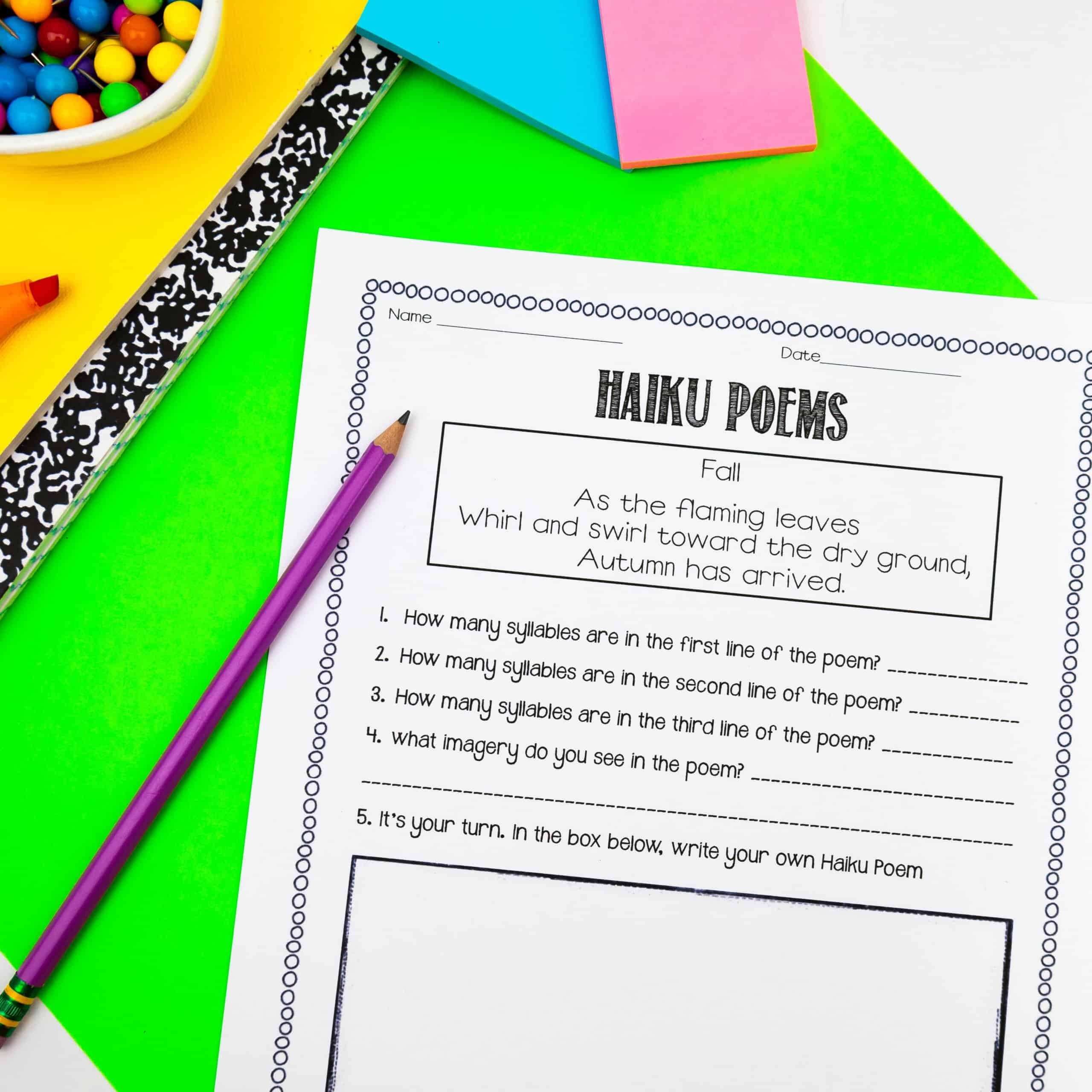

After introducing rhyme, I introduce meter, which is a unit of rhythm in poetry or the pattern of the beats. The difference in types of meter is which syllables are accented and which are not. This can become a bit complicated, so I primarily focus on finding the number of syllables in each line of a poem. A great way to do this is through Haiku poems. In a Haiku, the first line has five syllables, the second line has seven syllables, and the third line has five syllables. Show students several examples of Haikus written by other students and let students try their own.

Once students know the parts of a poem and how to read a poem, I like to dig a little deeper into comprehension. Each day we read a poem together and then break down the poem to completely understand the meaning of the poem. Then, students repeat the same steps with a poem that they’ve read with a group, partner, or individually.

Imagery & Figurative Language

It’s hard to teach poetry without incorporating imagery and figurative languge. Imagery is the elements in a poem that spark off the senses. This does not have to be just visual but can apply to any of the five senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell). A poet could simply state, “I see a flower”, but it is much more interesting to use techniques such as similes or metaphors to describe the flower. Read a few poems to students and have them think about the imagery within the poem(s). Two great examples are “At the Seaside” and “How Doth the Little Crocodile”.

Poems are an amazing source of figurative language, so when you’re reading poems you’re sure to encounter many examples of similes, metaphors, idioms, and even more types of figurative language. Continuously look for examples of figurative language in the poems you read.

These are great lessons to tie in with student writing. During that time, students can try writing their own poems. To raise the rigor, you can have students complete paired passages that incorporate poetry. I’ll share more about that soon! You can find the lessons above here.

Related Posts