Study selection

Our search yielded 2523 publications. After duplicates were removed, we screened 1809 records. Of these, 1782 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Ten further records were identified via our additional searches; one was eligible for full-text screening. Overall, 28 full-text records were assessed for eligibility [11,12,13, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Of these, 16 were eligible for analysis (see Fig. 1) [11,12,13, 40, 41, 43, 44, 47,48,49,50,51, 53, 55, 57]. Two of the studies were published in the same paper [11].

Excluded studies

We excluded 12 studies [35,36,37,38,39, 42, 45, 46, 52, 54, 56, 58] due to ineligible outcomes (did not investigate reasons for the decline in empathy; n = 8 [35, 37,38,39, 42, 46, 52, 56]), ineligible study design (non-qualitative study; n = 3 [45, 54, 58]), and ineligible participants (non-medical students; n = 1 [36]).

Study characteristics

The 16 included studies were from Europe, including the UK (n = 8), North America (n = 4), Asia (n = 3), and Africa (n = 1). All but one [50] listed the number of student participants. The total number of reported students included was 771 (mean 51.4, range 10–205). The year of publication ranged from 2010 to 2022. Most studies (n = 13) involved a single interview lasting between 35–90 min. Two studies involved multiple interviews; and one did not report how frequent or long the interviews were. Whether the medical school was graduate entry was rarely reported; however, it could be assumed that North American students were likely to be graduate entry medical students. The setting (medical school year) ranged from 2nd to final year, with most studies involving 4th- or 5th-year students. Only half of the studies reported detailed demographic characteristics. In these studies, between 50–84% of respondents were female. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the included studies.

Risk of bias in the included studies

Table 2 includes a summary of the risk of bias assessments. In five of the included studies, it was unclear whether they had obtained ethical approval [11,12,13, 43, 50]. One study had no areas of concern [48], and the rest had between one (n = 3) [12, 47, 55] and 8 (n = 1) [43] bias concerns. The most consistent concern (n = 14) was whether participants’ voices were adequately represented.

Results of the thematic syntheses

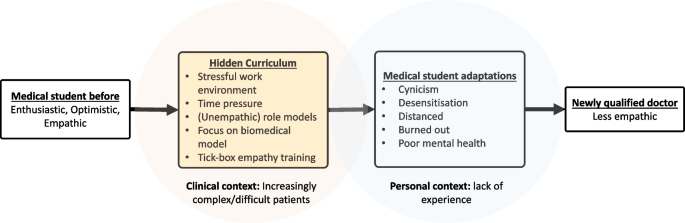

Changes in medical student empathy were reported to be influenced (usually reduced) by several factors. Four interpretive themes were developed as part of our synthesis: ‘complexity’, ‘hidden curriculum’, ‘acquired adaptations’, and ‘capacity limits’. Each was derived from 11 (descriptive) sub-themes (see Table 3 for a summary). ‘Complexity’ was derived from the difficulty of relating to the patients’ complexity, especially their socioeconomic situations and diseases. ‘Hidden curriculum’ was derived from ‘stressful organisational culture’, ‘formal teaching’, ‘role models’, ‘prioritisation of biomedical knowledge’, and (lack of) ‘encouragement’. ‘Acquired adaptations’ was derived from ‘cynicism’, ‘desensitisation’, and ‘distancing’. ‘Capacity limits’ was derived from ‘lack of experience’ and ‘limits on emotional capacity’. The themes appeared to be linked, with the hidden curriculum leading to adaptations such as cynicism that decrease empathy (see Fig. 2).

Complexity

As they transition through medical school training, students are exposed to increased patient and social complexity, which was reported to be a barrier to empathy in 10 studies [11,12,13, 40, 41, 44, 47, 55, 57]. While complexity was based on a single descriptive theme, we noted that it had many intertwined dimensions, ranging from the complexity of patients and diseases to the complexity of socioeconomic circumstances and values.

‘I sometimes find it difficult [to have empathy with] patients who suffer from dementia, are bedridden, need a lot of care or who no longer communicate with the people around them. I also find that one should also consider how much these people might actually still understand of what one communicates.’ [11]

‘Empathy can also make me feel guilty when I struggle to empathise with certain patients such as those with very different views to my own or patients… I feel are difficult.’ [47]

However, exposure to complexity was found to increase empathy in some students.

‘Meeting many patients with different diseases, different backgrounds and different individual needs, preferences and values was considered an important promoter of professional empathy. As a female student (no. 3) wrote: Meetings with patients both increased her ability to assume the patient´s perspective and developed her ability to express her empathy in a way that was adjusted to the individual patient.’ [57]

Hidden curriculum

The hidden curriculum (or informal curriculum) has been defined as the subtle, non-formal influence students witnessing (sometimes) unempathic role models, time pressure, the prioritisation of biomedical knowledge and cynicism (as a coping strategy) [59]. The hidden curriculum was explicitly mentioned in eight studies [11, 12, 44, 47,48,49, 51] and cited by an additional one [40] as a cause of empathy decline.

Stressful organisational culture

The working environment in which the students are immersed was noted as being stressful and, in some cases, different from the environment in the earlier phases of medical school. This theme came across consistently within 15 studies [11,12,13, 40, 41, 43, 44, 47, 49,50,51, 53, 55, 57]. This culture was caused by specific factors, such as workload, and an overly competitive environment.

‘Professional training was described as being cut-throat and competitive, hindered by administrative policies, long hours and the need to constantly maintain high level performance.’ [51]

Formal teaching

In 11 studies, formal empathy teaching was found to impact students’ ability to empathise [13, 40, 43, 44, 47,48,49,50, 53, 55, 57]. In most cases, the influence of teaching was believed to have a positive effect.

‘…it is good that they do it [empathy training] in the first and second year because we’re new and we’ve not had that sort of training before. Maybe like just before we start clinical [training]. So if we just had 1 day just sort of recapping things and I think that would be quite useful.’ [55]

However, the impact of the formulaic or ‘tick-box’ approach to empathy that is currently being encouraged in some medical schools to pass exams was found to detrimentally affect students’ ability to empathise.

‘Assessments were deemed to lead to a reductionist, or “tick box” approach to empathy. …in an OSCE [as Objective Structured Clinical Examinations], you’re just trying to tick a box, aren’t you? And you drop in a statement “oh that must be really hard?” and I think there is probably quite a lot of that. But then… everyone is under a lot of stress.’ [48]

Role models

In 12 studies [11, 13, 40, 41, 44, 47, 48, 50, 53, 55, 57], the way senior clinicians demonstrated empathy towards patients was reported to influence how students empathised with their patients.

‘Students felt that their empathy had improved only because of the positive role modelling by senior teachers. They mentioned that they learned empathy by observing them. One of the students commented: “I have no doctors in the family, so I came with zero knowledge, and whatever I came to know was because of our teachers and what I observed in the hospital through whatever they taught us. So, we only learn from them.”’ [40]

While positive role models encouraged empathy, negative role models had the opposite effect.

‘…there might be a barrier in so much as they don’t want to have anything to do with their patients, they’d just rather treat them and get on with it, which I don’t think is conducive to the best patient care that you can give someone, but a lot of doctors personally just don’t have great empathy skills or don’t have great communications skills in order to communicate their empathy.’ [55]

Prioritisation of biomedical knowledge

While there was no suggestion that biomedical knowledge was unnecessary, the prioritisation of theoretical knowledge over soft skills made it more difficult for some students to learn empathy. This was illustrated in 10 studies [11, 12, 40, 41, 44, 47, 49, 53, 55].

‘When one only focusses on the scientific aspect, learning facts by heart aspect, instead of focusing on the human aspect and the person behind the patient, always treating everything as just another case, then one works according to standard procedures. It definitely hinders empathy.’ [11]

(Lack of) Encouragement

In eight studies [11, 40, 41, 47, 50, 51, 53], students reported encouragement improved their ability to express empathy. This encouragement could come from peers or seniors.

‘However, most of the students felt motivated when encouraged by senior faculty members.’ [40]

‘FGDs [focus group discussions] among the medical student and resident groups revealed that their peers were the most influential factor in developing their humanistic characteristics. Having peers that reminded them to treat patients as human beings helped them to become humanistic physicians, as the desired behaviours would eventually become habits.’ [50]

However, not all encouragement was positive.

‘[We’re] not appreciated… We give advice… But why they do not listen, nah. So..you ignore yourself, why do we care for you?!’ [41]

Acquired adaptations

Students reported developing various ways of coping with the stress of medical school, which in turn influenced their ability to empathise with patients. These were: cynicism, desensitisation, and professional distancing.

Cynicism

Six studies reported that students found it challenging to maintain empathy for all patients, so they developed a sense of cynicism to protect themselves from burnout [12, 44, 47, 48, 51, 57].

‘Also, you can become more cynical as well… if you are in GP and the GP is like “this patient coming in just really doesn’t help themselves” then that impacts your empathy the other way.’ [47]

Desensitisation

In seven studies [12, 41, 43, 44, 48, 53, 55], students’ extended exposure to emotionally taxing experiences throughout their training caused them to become desensitised and consequently reduced their ability to empathise.

‘Since the beginning of the year, we get to see sick patients and get desensitised. We are dealing with very serious patients all the time and we don’t have the time to empathise with each patient.’ [43]

Professional distancing

Nine studies [11, 12, 44, 47, 48, 53, 55, 57] found that to be able to act professionally, students emotionally distanced themselves from patients, which hindered their ability to empathise with them.

‘Developing a certain emotional distance from the patient, and avoiding too much empathy was widely understood as being a key component of being a professional. One student was very conscious that she should not be a friend, or behave as a family member, but instead create a professional distance. The student vigorously tried to create distance, and avoided thoughts like “What if it was me, or my sister.”’ [12]

Capacity limits

A range of factors limited students’ ability to empathise. There was no suggestion that these limits were inherent or insurmountable; however, a lack of experience and emotional capacity limits were reported as barriers to empathy in many of included studies.

Experience

Students had a range of previous experiences that affected their ability to empathise when they entered the clinical phase of their education. This theme was apparent in 14 studies [11, 13, 40, 41, 44, 47,48,49,50,51, 53, 55, 57]. The differing experiences included professional experience (exposure to real patients) and personal experience (medical students are generally healthier and from more privileged socio-economic backgrounds than many of the complex patients they treat). The lack of experience can lead to insecurity. Furthermore, the increased pressure of medical school limited opportunities for experiences outside medical school. This, in turn, reduced students’ experiences interacting with patients.

‘I also remember that it is difficult to be empathetic when you do not understand the situation or the disease. I was at the rheumatology ward early in the early part of the course in clinical medicine and had to perform a bedside investigation of a girl of my age who had just received a diagnosis of SLE. She had only had one or two non-severe attacks of the disease, but she had many questions about long-term prognosis and fertility, and she started to cry in front of me. At this time, I did not know much about SLE, medication and the long-term effects of the disease and had never had concrete thoughts about pregnancy or about chronic disease in young people. I found it very difficult to understand her immediately and to act empathetically.’ [57]

However, experience was found to promote empathy in some cases.‘.. one that can increase empathy is… personal experience, because I had fractured, and I was treated and how it felt, so, me and my fractured patients are tended to care.’[41]

Limits on emotional capacity

In seven studies [11, 13, 40, 41, 47, 48], students’ empathetic abilities were limited due to personal stresses that reduced their emotional availability.

‘There is (..) a limit regarding a person ‘s emotional capacity, [empathy is easier when one] doesn’t have additional personal stress, three friends with problems and a sick father or something else.’ [11]

Exploring heterogeneity

There was not enough data, and reporting was not sufficiently complete to formally investigate sources of heterogeneity. However, we did note a few potential causes of heterogeneity. Medical students from the US or Canada, who were more likely to be older graduate entry medical students, did not report that life experience and personal maturation impacted their ability to empathise.

While we did not have enough studies from different continents to conduct subgroup analyses by country or continent, the three studies from Asia were represented in all four analytical themes, while the study from Africa was represented in three of the four analytical themes.

Certainty of evidence

The results of our assessments regarding the overall quality of evidence are presented in Supplementary Table 1. We had a high level of confidence in the evidence for ‘complexity’, ‘stressful organisational culture’, ‘role models’, and ‘prioritisation of biomedical knowledge’. ‘Formal teaching’, ‘encouragement’, ‘desensitisation’, ‘professional distancing’, ‘experience’, and ‘limits to emotional capacity’ were supported by moderate-quality evidence. ‘Cynicism’ was the only theme supported by low-quality evidence, and no themes were supported by very low-quality evidence.